Inner-City Violence in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Harsh criminal-justice policies have thrown America's poorest urban communities into chaos.

Over the summer, media outlets across the country fixated on the mounting death toll of young people in inner cities across America. “11 shot, including 3-year-old boy, as Chicago gun violence worsens,” read the large headline of one major U.S. newspaper, while another, the Chicago Tribune, published a painfully graphic photo essay that chronicled the degree to which gun violence in particular had shocked and destabilized entire neighborhoods in 2014.

This fall, television reporters still stand nightly outside of dimly-lit apartment buildings and row houses, telling yet more stories of children felled by bullets and showing new heartbreaking scenes of mothers wracked by sobs. And yet, other headlines suggest that this nation is far safer and much less violent than it used to be. They note that gun violence has plummeted a startling 49 percent since 1993 and, aside from some brief spikes and dips in the last few years, most policymakers seem to feel quite good about America’s overall crime rate, which is also at a noticeable low.

Why is it then that some American neighborhoods, from the south side of Chicago to the north side of Philadelphia to all sides of Detroit, still endure so much collective distress? Might there be something about these particular neighborhoods, pundits wonder, that make them more prone to violence?

According to one well-respected scholar, "high rates of black crime" continue to exist despite declining crime rates nationally because African Americans live in highly segregated and deeply impoverished neighborhoods. Not only does his work suggest that both segregation and poverty breed violence but, more disturbingly, that the ways in which poor blacks decide collectively and individually to protect themselves seems only to "fuel the violence," and gives it "a self-perpetuating character."

Segregation and poverty are indeed serious problems today, and too many of America’s poorest all-black and all-brown communities also suffer a level of violence that, if one disregards the horrific killing sprees in places like Columbine, Seattle, or Sandy Hook, is largely unknown in whiter, more affluent neighborhoods. Whereas the violent crime rate in the mostly black city of Detroit was 21.23 per 1,000 (15,011 violent crimes) in 2012, that same year the virtually all-white city of Grosse Point, Michigan nearby reported a rate of only 1.12 per 1,000 (6 violent crimes).

Notwithstanding such seemingly damning statistics, though, we have all seriously misunderstood the origins of the almost-paralyzing violence that our most racially-segregated communities now experience and, as troublingly, we have seriously mischaracterized the nature of so much of the violence that the residents of these communities suffer.

To start, locating today’s concentrated levels of gun violence in hyper-segregation and highly concentrated poverty is quite ahistorical. As any careful look at the past makes clear, neither of these social ills is new and, therefore, neither can adequately explain why it is only recently that so many children of color are being shot or killed in their own communities.

Indeed, throughout the twentieth century, racially-segregated communities have been the norm. Everything from restrictive covenants to discriminatory federal housing policies ensured that throughout the postwar period, neighborhoods in cities such as Detroit or Chicago would be either all white or all non-white and, until now, none of these segregated spaces experienced sustained rates of violence so completely out of step with national trends.

To suggest, as both scholars and the media have, that the violence experienced by all-black or all-brown neighborhoods today stems in large part from their residential isolation is problematic for other reasons as well. It leads some to suspect that if people of color simply spent more time with white people, lived next to them, and went to school with them, they would be less violent—they would perhaps learn better ways to resolve disputes and deal with stress and anger. Again, though, history belies this logic.

White Americans also have a long history of violence—not only when asked to share residential space with African Americans or even to treat them as equals in schools or on the job, but also when nary a person of color is near. From the lynching of blacks in the Jim Crow era to the crimes committed against African Americans every time they tried to move onto a white block after World War I and World War II, ugly incidents of white violence were both regular and unremarkable. Even among those who look just like them, whites historically have engaged in a variety of violent behaviors that would make many shudder—from their propensity to engage in brutal duels and to “eye gouge” their fellow whites in the decades before the Civil War, to their involvement in mass shootings in more recent years.

Just as hyper-segregation doesn’t explain the violence that so many have to endure today in America’s inner city communities while still raising children, attending church, and trying to make ends meet, neither does highly-concentrated poverty. Because of their exclusion from virtually every program and policy that helped eventually to build an American middle class, non-whites have always had far less wealth than whites. From the ability to maintain land ownership after the Civil War, to the virtual guarantee of welfare benefits such as Social Security and FHA loans during the New Deal, to preferential access to employment and housing in the postwar period, white communities have always had considerably more economic advantage than communities of color. And yet, no matter how poor they were, America’s most impoverished communities have never been plagued by the level of violence they are today.

But if neither racial segregation nor the racial poverty gap can account for the degree to which poor communities of color are traumatized today, then what does? What is altogether new is the extent to which these communities are devastated by the working of our nation’s criminal justice system in general and by mass incarceration in particular.

Today's rates of incarceration in America's poorest, blackest, and brownest neighborhoods are historically unprecedented. By 2001, one in six black men had been incarcerated and, by the close of 2013, black and Latino inmates comprised almost 60 percent of the nation’s federal and state prison population. The numbers of incarcerated black women are also stark. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, young black women ages 18 to 19 were almost five times more likely to be imprisoned than white women of the same age in 2010.

When President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Law Enforcement Assistance Act in 1965—legislation which, in turn, made possible the most aggressive war on crime this nation ever waged—he was reacting not to remarkable crime rates but to the civil rights upheaval that had erupted nationwide just the year before. This activism, he and other politicians believed, represented not participatory democracy in action, but instead a criminal element that would only grow more dangerous if not checked.

Notably, the national policy embrace of targeted and more aggressive policing as well as highly punitive laws and sentences—the so-called “War on Crime” that led eventually to such catastrophic rates of imprisonment—predated the remarkable levels of violence that now impact poor communities of color so disproportionately.

In fact, the U.S. homicide rate in 1965 was significantly lower than it had been in several previous moments in American history: 5.5 per 100,000 U.S. residents as compared, for example, with 9.7 per 100,000 in 1933. Importantly, though, whereas the violent crime rate was 200.2 per 100,000 U.S. residents in 1965, it more than tripled to a horrifying 684.6 per 100,000 by 1995. Though mass incarceration did not originate in extraordinarily high rates of violence, mass incarceration created the conditions in which violence would surely fester.

The quadrupling of the incarceration rate in America since 1970 has had devastating collateral consequences. Already economically-fragile communities sank into depths of poverty unknown for generations, simply because anyone with a criminal record is forever “marked” as dangerous and thus rendered all but permanently unemployable. Also, with blacks incarcerated at six times and Latinos at three times the rate of whites by 2010, millions of children living in communities of color have effectively been orphaned. Worse yet, these kids often experience high rates of post-traumatic shock from having witnessed the often-brutal arrests of their parents and having been suddenly ripped from them.

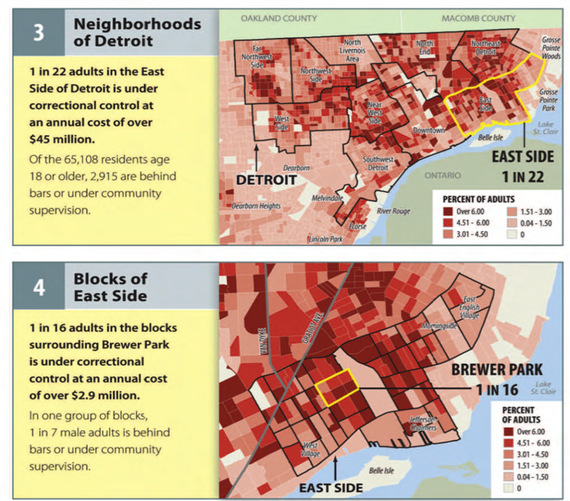

De-industrialization and suburbanization surely did their part to erode our nation’s black and brown neighborhoods, but staggering rates of incarceration is what literally emptied them out. As this Pew Center of the States graphic on Detroit shows, the overwhelmingly-black east side of the Motor City has been ravaged by the effects of targeted policing and mass incarceration in recent years with one in twenty-two adults there under some form of correctional control. In some neighborhoods, the rate is as high as one in 16.

Such concentrated levels of imprisonment have torn at the social fabric of inner city neighborhoods in ways that even people who live there find hard to comprehend, let alone outsiders. As the research of criminologist Todd Clear makes clear, extraordinary levels of incarceration create the conditions for extraordinary levels of violence. But even mass incarceration does not, in itself, explain the particularly brutal nature of the violence that erupts today in, for example, the south side of Chicago. To explain that, we must look again carefully and critically at our nation’s criminal justice system.

The level of gun violence in today's inner cities is the direct product of our criminal-justice policies—specifically, the decision to wage a brutal War on Drugs. When federal and state politicians such as New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller opted to criminalize addiction by passing unprecedentedly punitive possession laws rather than to treat it as a public health crisis, unwittingly or not, a high level of violence in poor communities of color was not only assured but was guaranteed to be particularly ugly. This new drug war created a brand-new market for illegal drugs—an underground marketplace that would be inherently dangerous and would necessarily be regulated by both guns and violence.

Indeed, without the War on Drugs, the level of gun violence that plagues so many poor inner-city neighborhoods today simply would not exist. The last time we saw so much violence from the use of firearms was, notably, during Prohibition. “[As] underground profit margins surged, gang rivalries emerged, and criminal activity mounted [during Prohibition],” writes historian Abigail Perkiss, “the homicide rate across the nation rose 78 percent…[and] in Chicago alone, there were more than 400 gang-related murders a year.”

As important as it is to rethink the origins of the violence that poor inner city residents still endure, we must also be careful even when using the term “violence,” particularly when seeking to explain “what seems to be wrong” with America’s most disadvantaged communities. A level of state violence is also employed daily in these communities that rarely gets mentioned and yet it is as brutal, and perhaps even more devastating, than the violence that is so often experienced as a result of the informal economy in now-illegal drugs.

This is a violence that comes in the form of police harassment, surveillance, profiling, and even killings—the ugly realities of how law enforcement wages America’s War on Drugs. Today, young black men today are 21 times more likely than their white peers to be killed by the police and, according to a recent ProPublica report, black children have fared just as badly. Since 1980, a full 67 percent of the 151 teenagers and 66 percent of the 41 kids under 14 who have been killed by police were African American. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, police officers shot and killed fifteen teens running away from them; all but one of them black.

This is the violence that undergirded the 4.4 million stop-and-frisks in New York City between 2004 and 2014. This is the violence that led to the deaths of black men and boys such as Kimani Gray, Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, Oscar Grant, and Michael Brown. This is the violence that led to the deaths of black women and girls such as Rekia Boyd, Yvette Smith, and 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones. And this is the violence that has touched off months of protests in Ferguson, Missouri just as it also touched off nearly a decade of urban rebellions after 1964.

A close look at the violence that today haunts America’s most impoverished and most segregated cities, in fact, fundamentally challenges conventional assumptions about perpetrators and victims. America’s black and brown people not only don’t have a monopoly on violence, but, in fact, a great deal of the violence being waged in their communities is perpetrated by those who are at least officially charged with protecting, not harming, them. As residents of Ferguson well know, for example, in the same month that Michael Brown was shot to death by a police officer, four other unarmed black men were also killed by members of law enforcement.

Indeed, the true origins of today’s high rates of violence in America’s most highly segregated, most deeply impoverished, and blackest and brownest neighborhoods—whoever perpetrates it—are located well outside of these same communities. Simply put, America’s poorest people of color had no seat the policy table where mass incarceration was made. But though they did not create the policies that led to so much community and state violence in inner cities today, they nevertheless now suffer from them in unimaginable ways.