Deadly American Extremism: More White Than Muslim

White supremacists and anti-government radicals are responsible for twice as many deaths in the U.S. as jihadists since 9/11.

It’s an accident of fate that Dzokhar Tsarnaev’s formal sentencing for the Boston Marathon bombing is happening just now, as the U.S. continues to reel from the Charleston massacre. Tsarnaev—Rolling Stone cover and teenage apologists aside—is a stereotypical face of terrorism in the 2010s: An extremist Muslim, residing and radicalized in the U.S., and acting alone or in a small cell.

In fact, though, most lethal political violence since September 11 has come in the form of attacks by white supremacists, anti-government extremists, and the like, according to an analysis by New America. It’s not even close: Jihadists have killed 26 people, versus 48 by what New America calls “right-wing extremists.”

In that way, Dylann Roof is far more representative of political violence in 21st century America than Dzokhar Tsarnaev could ever be.

The numbers are a little more nuanced, and interesting, than that. The most deadly event counted in the study is the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, an jihadist massacre that killed 13—far more than any other attack of either kind (the closest to it is Charleston). Take that out and the numbers are even more disparate.

That isn’t to say that Islamist attacks aren’t a problem. A total of 277 people have been charged with jihadist terrorism, versus 183 nonjihadists. That ought not to be entirely surprising: Since 9/11, the United States government and local authorities have made preventing Islamist terror a primary goal. A Pew poll last September found that 53 percent of Americans are very concerned about Islamic terrorism in the U.S., with another 25 percent somewhat concerned. To fight this threat, authorities have expended great sums of money, deployed vast resources, tested the limits of civil liberties and, in at least some cases, have exceeded them according to courts. Some of those measures may well have been worth the cost and saved lives, though some almost certainly have not.

One reason the more aggressive steps have, until recently, not raised widespread public objections is that the people coming in for the most scrutiny tend to be minorities or people of color with less political clout. Compare Muslim Americans’ accounts of airport profiling, or the way the NYPD infiltrated Muslim communities, to the way that armed, white, anti-government agitators like Cliven Bundy and his backers were treated with kid gloves—even though, numerically, Bundy’s ideological fellow travelers are at least as dangerous.

The disparity is clear to law-enforcement officials, The New York Times notes:

If such numbers are new to the public, they are familiar to police officers. A survey to be published this week asked 382 police and sheriff’s departments nationwide to rank the three biggest threats from violent extremism in their jurisdiction. About 74 percent listed antigovernment violence, while 39 percent listed “Al Qaeda-inspired” violence, according to the researchers, Charles Kurzman of the University of North Carolina and David Schanzer of Duke University.

September 11 looms extremely large in the collective national imagination about terrorism, and for good reason. It was a traumatic event, played over and over again on television, and nearly 3,000 lives were lost.

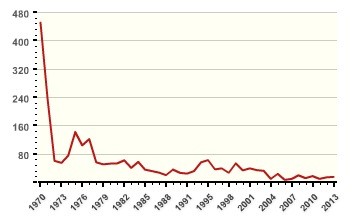

But that’s just the problem: Since 9/11, Americans have lost sight of what the daily reality of terrorism looks like. Most deadly incidents of terrorism or political violence result in fewer than ten fatalities. Terrorism is getting significantly less common stateside, believe it or not—as this chart from the Global Terrorism Database shows:

Moreover, most acts of terrorism are committed not with bombs or improvised weapons, but with firearms. And that points to an even greater point: The number of gun deaths in the United States in 2015 is projected to reach, by one estimate, 33,000. That’s more than 11 September 11s in a single year. Even the number of incidents in the New America report involving gunfire—68 of the 74 deaths—shrinks in comparison to the annual toll of gun violence. Yet there’s far more political will to address terrorism than guns.

Gun violence also offers a more concrete target than “terrorism”—a conflicted term, loaded with meanings and disagreements, but abstract by any definition. (If guns don’t kill people, as the old slogan has it, it must be true that terrorism doesn’t either.) That hasn’t stopped anti-terrorism legislation, but gun-control legislation is frequently criticized as overly broad or too diffuse.

New America’s report focuses in on terrorism specifically—although, interestingly, it doesn’t explicitly define the term. Generally, experts require terrorism to be not only ideologically motivated violence, but violence with a broader goal. That means New America excludes the shooting of three Muslims in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, by a man with a history of pejorative statements about Muslims and threats. It is hard to review the facts and believe he was simply angry over a parking space, as police initially suggested, yet he also seems to have had no broader ideological motivation or cause. This example makes the case that perhaps it might make more sense to think in terms of “political violence” than in terms of “terrorism.” (Many of the largest firearm killings have no political valence at all—such as the 2013 Navy Yard shooting in Washington, or the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting.)

In any case, the figures in this report make a compelling case for Americans to reconsider what constitutes the largest terrorist threat—and to place that threat in perspective against the much larger threat of gun violence writ large.