Editor’s Note: Louis A. Perez Jr. is the J. Carlyle Sitterson professor of history and the director of the Institute for the Study of the Americas at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Among his books are “Cuba in the American Imagination: Metaphor and the Imperial Ethos” and “Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Louis Perez: In death, Castro passes into status of historical subject impossible to discuss dispassionately for years to come

He says Castro defied America; even with his death Cuba not likely to bend to demands of US with incoming Trump administration

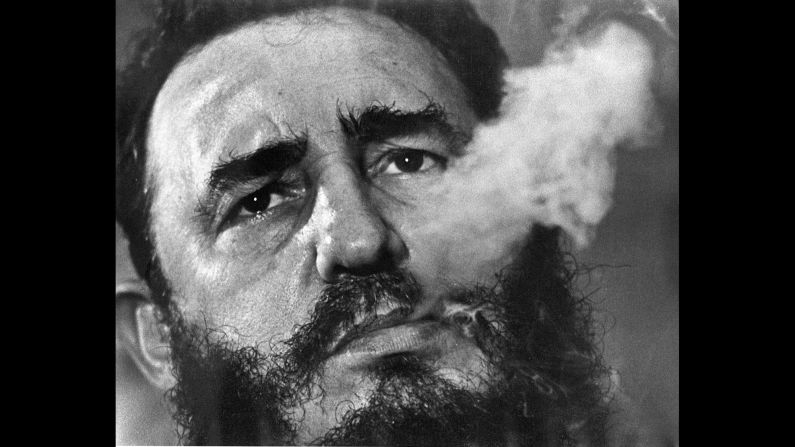

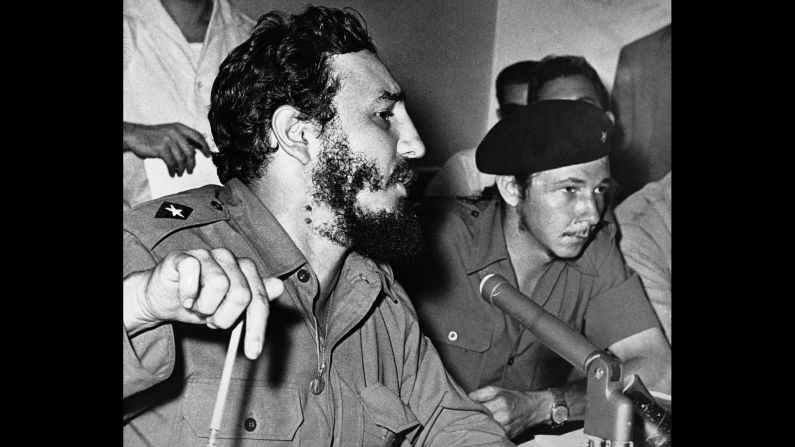

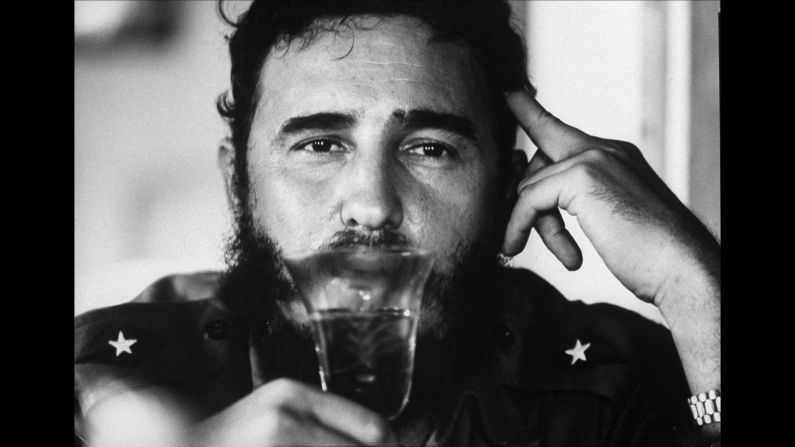

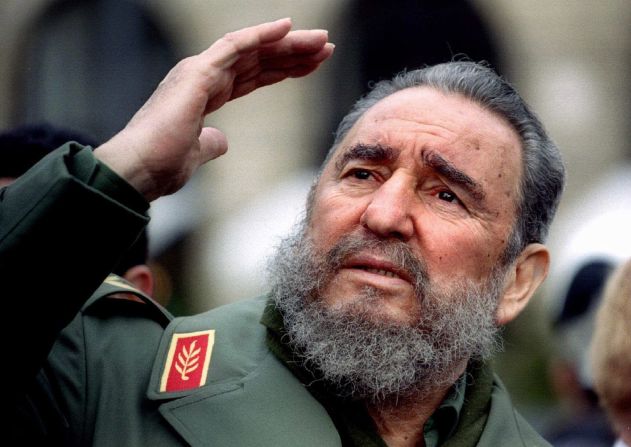

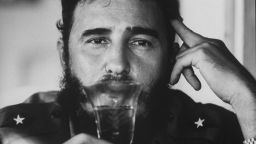

Fidel Castro Ruz, the political personality, has died. Fidel Castro, the historical persona, has been born. He passes from the present into the past, to serve as an enduring historical subject of debate and dispute, about whom dispassion will be impossible for years to come. Fidel Castro was not a man about whom one is likely to be neutral.

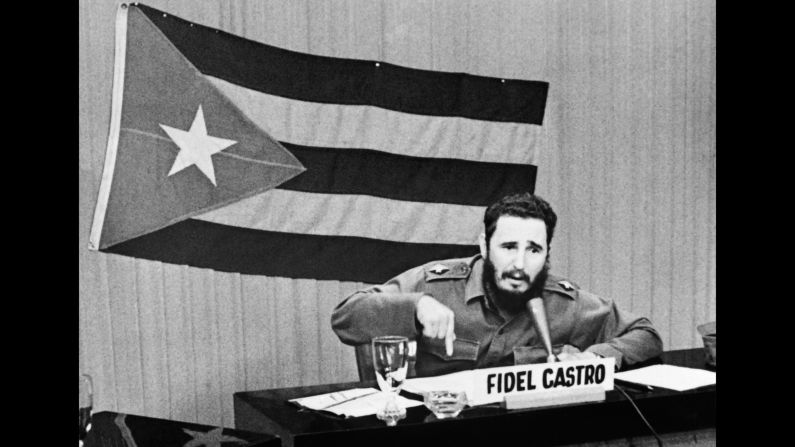

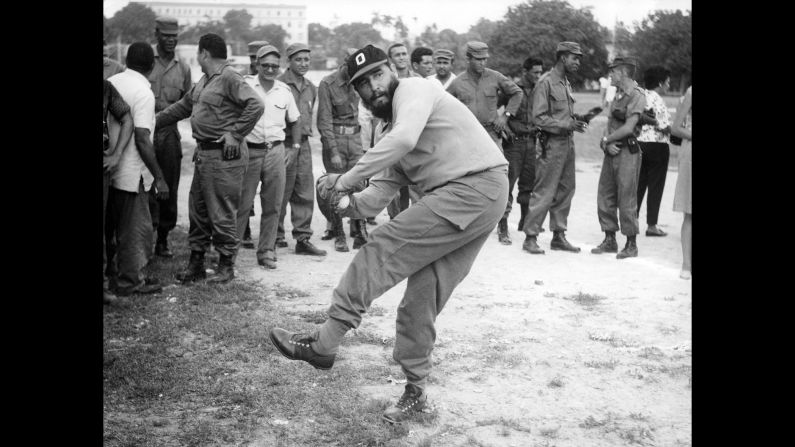

Fidel is a metaphor. He is a Rorschach blot upon which to project fears or hopes. A prism in which the spectrum of colors refracted out has to do with light that went in. He is a point of view, loaded with ideological purport and political meaning. A David who survived Goliath. A symbol of Third World intransigence against First World domination.

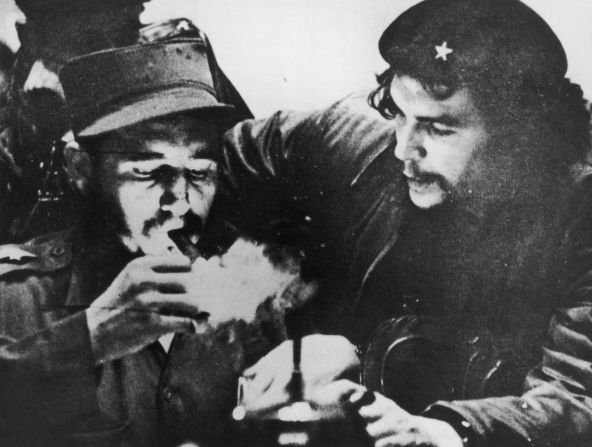

But it is also possible to discuss the historical “essences” of Fidel Castro. He emerged out of a history shaped by a century of Cuban national frustration, heir to a legacy of unfulfilled hopes for national sovereignty and self-determination, aspirations that put Cuba on a collision course with the United States. The collision of the early 1960s served to fix the trajectory of the 50 years of ruptured relations that followed.

Former Cuban leader Fidel Castro dies

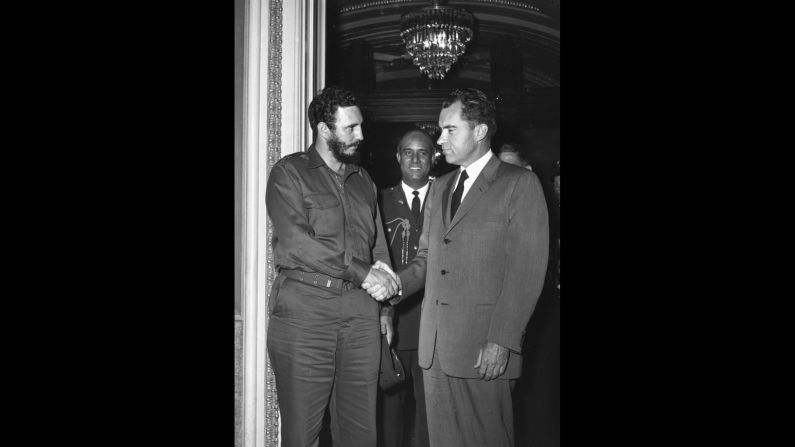

There was something deeply personal about the Cuba-U.S. estrangement. Fidel Castro offended American sensibilities. The sheer effrontery of Castro’s challenge to the United States was breathtaking: defiant, strident, often virulent denunciations of the United States, hours at a time, day after day, stretching into weeks and months, and years.

Castro’s invective was more than adequately reciprocated by American vilification. Fidel Castro was held personally responsible for almost all the challenges the United States faced in Central and South America, in the Caribbean, in Africa. Castro was transformed simultaneously into an anathema and phantasma, unscrupulous and perhaps unbalanced, possessed by demons and given to evil doings.

He defied years of US efforts at regime change and his very defiance transformed him into something of an enduring national obsession. Castro occupied a place of almost singular distinction in that netherworld to which the United States banished its demons.

He was the man Americans loved to hate; political conflict personalized; decades of frustration over the US’ unsuccessful attempts to force Cuba to bend its will – all this vented on one man. Certainly, scores of assassination plots against the life of Castro could not have made American wrath any more personal.

And, yes: the missiles of October 1962. Castro would never be forgiven. It is highly unlikely that any American administration could have embarked on a US-Cuba rapprochement with Fidel Castro in power.

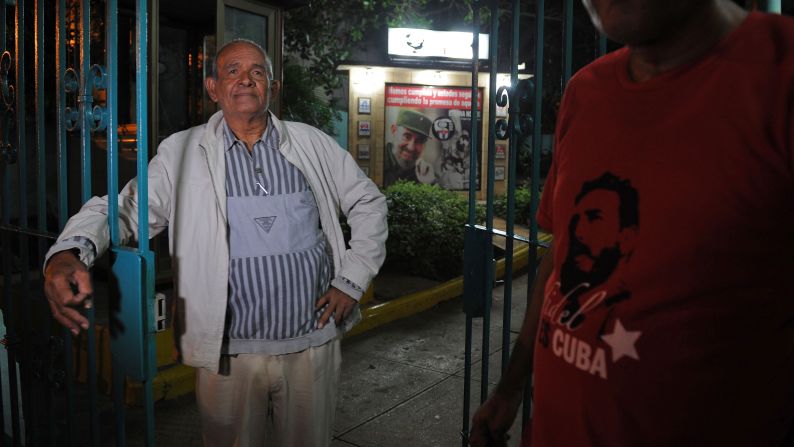

His death leaves something of a void in Cuba. Not in the form of a power vacuum, of course, but as the absence of a voice and the loss of a presence.

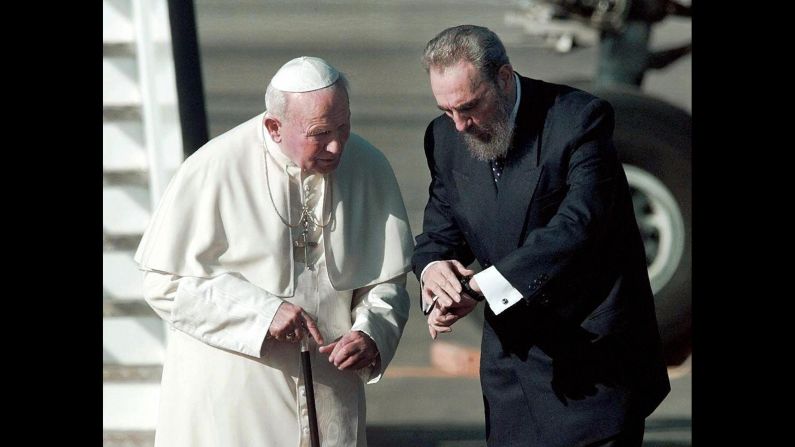

Even old, feeble and in failing health, beset with infirmities, and perhaps with traces of senility, Fidel continued to discharge the role of symbol. He was suspicious of President Barack Obama’s rapprochement initiatives. He no doubt would have been alarmed by the campaign rhetoric of President-elect Donald Trump.

The Republican Party platform inaugurated the 2016 electoral campaign prepared to welcome “Cuba back into our hemispheric family after their corrupt rulers are forced from power and brought to account for their crimes against humanity.” The President-elect vowed to roll back all “concessions” made to Cuba unless the “regime meets our demands,” demands that include “religious and political freedom for the Cuban people.”

At this stage of US-Cuba relations, the very proposition of American “demands” on Cuba bode ill for continued normalization. A people who have endured 60 years of privation over the course of 11 presidential administrations in defense of national sovereignty and self-determination will not likely acquiesce to demands of a 12th administration.

In passing from the present to the past, Fidel will henceforth speak from the grave.