By Thomas J. Brown

Columbia comes logically to its current position at the forefront of the national debate over Confederate memorials. The city has a good claim to be both the place of birth and the place of death for the Confederacy. The antebellum South Carolina College, now the University of South Carolina, was the academic hothouse of proslavery secessionist ideology. The political culture centered on the state capital provided the institutional framework through which the disunion campaign developed. The culminating secession convention met at First Baptist Church on December 17, 1860. Fear of a smallpox outbreak caused the delegates to finish their business in Charleston, but before they left Columbia they adopted a unanimous resolution to break from the United States.

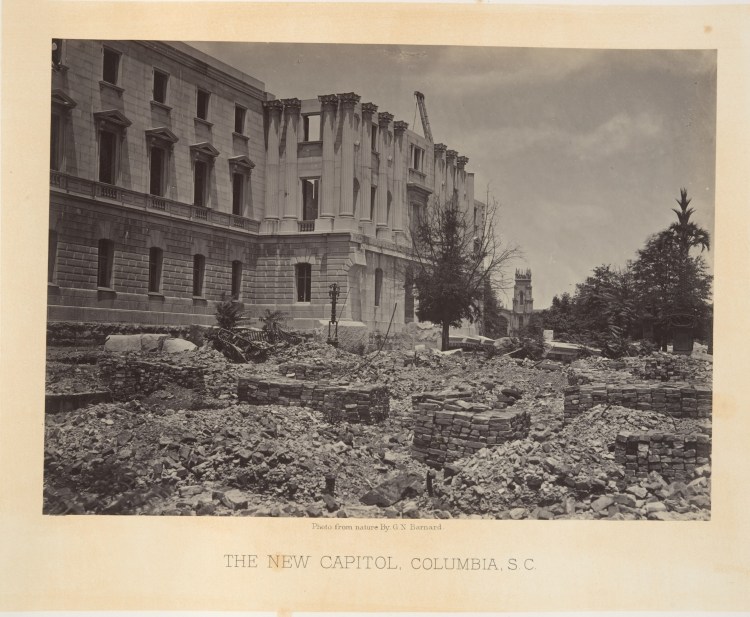

Union soldiers who reached Columbia on February 17, 1865 after almost four years of war were eager to hold the city accountable for its leadership in the rebellion. The fires that destroyed the state house built in the 1790s and at least one-third of all other buildings in town resulted in part from high winds and local failure to destroy the stockpiles of alcohol that intoxicated federal troops and the cotton bales that spread flames, but the burning of Columbia served as an exclamation mark for the triumphant Union policy of hard war.[1] General William T. Sherman declared a few months later that “from the moment my army passed Columbia S. C. the war was ended.”

Confederate memorials abound in Columbia in all forms, including cemeteries, statues, historic buildings, memorial trees, roadside plaques, and names of streets, parks, schools, and other locations. My book Civil War Canon: Sites of Confederate Memory in South Carolina (University of North Carolina Press, 2015) touched on many aspects of this profusion in a close look at the places of national significance–the grave of Confederate poet laureate Henry Timrod at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, the monuments to the exemplary Confederate man and woman at the state house, and the display of the Confederate battle flag at the state house.

It was no coincidence that two of those three chapters focused on the state house grounds, by far the most important public space in town. The state house has been crucial to the relationship between Columbia and the Confederacy since the decision to build a new capitol amid the acceleration of the secession movement in the 1850s. Located at the corner of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway and the Robert E. Lee Memorial Highway, the grounds present a remarkable array of Confederate commemorations, including flamboyant dramatization of the wounds suffered by the building in Sherman’s wartime attack.[2] Dell Upton’s What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South (Yale University Press, 2015) thoughtfully analyzes the ways in which this Confederate landscape inflects the African American History Monument unveiled at the state house in 2001. The tension between conflicting memorials epitomizes the challenge of reconfiguring the racial environment to realize the ideals of the civil rights movement.

Columbia opened a new chapter in the history of Confederate memorialization with the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the state house grounds in July 2015. This decision responded to Columbia native Dylann Roof’s murder of nine African Americans at a Bible study session in Charleston and the subsequent discovery of a website at which Roof had recorded his hopes to start a race war and posted photographs of himself posing with the battle flag. To be sure, the South Carolina legislature aimed not to begin but to close a chapter by removing the flag; state celebrations of the southern cross had by then ended at all other capitols except through its incorporation in Mississippi’s state flag. But in the wake of the church massacre, the recoil against Confederate remembrance extended from the battle flag to monuments. Although protesters had begun to “tag” monuments after the killings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, calls for removal started to gather substantial momentum when New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu endorsed the “Take ‘Em Down NOLA” campaign four days after the discovery of Roof’s website. As that movement developed over the next two years and spread widely after the white supremacist rallies in Charlottesville in 2017, Columbia stood at the vanguard in the defense of Confederate memorials and even in the creation of new Confederate memorials.

South Carolina has furnished the model for the state legislation that has suppressed debate over the future of Confederate monuments in hundreds of southern cities and counties. The Heritage Act of 2000, which moved the battle flag from the state house dome to a position near the state monument to the Confederate dead, provided that no war memorial (or Native American history or African American history memorial) installed on the property of the state or any political subdivision “may be relocated, removed, disturbed, or altered” and that no public site “named for any historic figure or historic event may be renamed.” This measure was much more purposeful and airtight than the Virginia law of 1904 and amendment of 1997 at issue in the recent controversy in Charlottesville. The South Carolina statute even purported to require a two-thirds vote for modification or repeal, despite the dubious enforceability of such provisions. Georgia followed suit in 2001 in conjunction with the controversy over the southern cross in its state flag, and Mississippi enacted parallel legislation in 2004. North Carolina adopted such a measure two weeks after South Carolina took down its Confederate battle flag in 2015. Tennessee, which had established restrictions in 2013, made them more difficult to overcome in 2016. Alabama passed a similar law in May 2017. The strategy has shifted authority over monuments in most of the former Confederacy from the wide variety of local communities to Republican-controlled state legislatures.

The experience of Columbia suggests the efficacy of the statutory regime in stifling opposition to Confederate remembrance. The legislative decision to raise the battle flag at the soldier monument in 2000, rather than removing it from the state house grounds, was opposed by twenty-two of the twenty-six black members of the House of Representatives and drew steady criticism from Columbia residents in the following fifteen years. Even the coach of the University of South Carolina football team, a stalwart of the local establishment, called for removal of the flag in 2007. The legislature remained adamantly committed to foreclosure of debate and did not revisit possible removal of the flag until forced to do so after the horrific murders at Emanuel AME church, in which one of the victims was a state senator. The region-wide laws that bar alteration or removal of memorials seem likely to eviscerate municipal reconsideration of Confederate monuments across the heart of the South, despite extraordinary examples of defiance in Durham, Memphis, and possibly Charlottesville.

Even apart from the suppressive legislation, Columbia illustrates the special powerlessness of a capital city to act on its residents’ opposition to icons of white supremacism. The Heritage Act of 2000 does not apply to the local monuments that have lately been most controversial, the state house tributes to Ben Tillman and J. Marion Sims. Neither work is what the Heritage Act calls a “War Between the States” memorial, though both men typified Confederate racial ideology. Disability prevented Tillman from serving in the Confederate army before he began his political career as a proponent of disfranchisement, segregation, and lynching. Sims left South Carolina for New York in the 1850s after his gynecological experiments on enslaved women helped him become the leading specialist in the country, and he decided to sit out the Civil War in Europe. Despite recent protests (and the plan of a New York City commission to remove a Sims statue in Central Park), these embodiments of white supremacism are probably as safe at the South Carolina state house as the marble figure of a Confederate soldier who continues to stand where the battle flag flew until July 2015.

In this season of iconoclasm, Columbia is instead focused on the installation of new Confederate memorials. Two projects have attracted national attention. Republican legislators Bill Chumley and Mike Burns, both of whom voted against removal of the Confederate battle flag in 2015, have introduced legislation to create an “African-American Confederate Veterans Monument Commission” that would redress the supposed neglect of black South Carolinians who supposedly took up arms for the proslavery republic. When told that extensive historical research on this precise topic has shown that no black South Carolinians fought for the Confederacy and that African Americans who labored in non-combatant roles were enslaved or pressed into duty without pay, the legislators told a newspaper reporter that “we don’t see that’s a problem.” With little prospect of passage, the proposal illustrates the aggressively provocative white supremacism and contempt for fact-based decision-making typical of the Republican party at the state as well as the federal level.

The older project stems from the removal of the Confederate battle flag at the state house in July 2015. The General Assembly provided that “upon its removal, the flag shall be transported to the Confederate Relic Room for appropriate display.” Separate legislation that took effect around the same time placed the Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum under the control of a commission composed of a member chosen by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, another chosen by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, three more appointed by the governor, two others appointed by the president of the senate, and finally, two members appointed by the speaker of the house. Taking its cue from legislators who had resisted removal of the flag at the state house and hoped to exhibit it alongside the Relic Room’s collection of wartime flags in a reverential setting, the commission asked the General Assembly in December 2015 for a $5.3 million appropriation and a 50% increase in annual operating expenditures to open a new wing in which the flag removed from the state house would be displayed in front of a jumbo-sized electronic screen that scrolled the names of the 22,000 (white) South Carolinians who died in the Confederate army. Despite widespread ridicule and the refusal of the state legislature to consider such a grand expenditure, the commission voted again in January 2017 to “vigorously advocate” its proposal.

Recent news reports indicate, however, that the commission may have become amenable to a plan set forth at the outset by Relic Room director Allen Roberson to seek an appropriation of approximately $400,000 to convert vacant offices into display space for the state house flag. The shift is interpretive as well as budgetary. Perhaps more alert than the commission to the implications of presenting the Dylann Roof flag alongside Confederate soldiers’ flags, Roberson argues that “the flag needs to be displayed separately from the military theme… It’s more of a political artifact.” He has suggested that the exhibition may trace the story of the southern cross from the war years through the present, with full attention to the campaign that brought removal of the flag from the state house dome in July 2000 and the circumstances that prompted its removal from the state house grounds in July 2015.[3] The Relic Room commission will decide at its upcoming February 15 meeting whether to present Roberson’s plan to the state legislature.

The discussions at the Confederate Relic Room prefigure, though in a different form, the debates likely to take place in many communities over the fate of Confederate memorials removed from public display and the addition of fresh contextual interpretation to Confederate memorials that remain on public display. For citizens of Columbia, the initiative at the Relic Room–like the statutory ban on alteration or removal of monuments–underscores legislative dominance in the capital landscape of remembrance. City residents and officials will need to be more creative to participate fully in the national reckoning with the Confederate legacy.

Picture at top: Drawing of Union Troops raising the American flag over the original South Carolina State House, illustration by William Waud appearing in Harper’s Weekly 9, April 8, 1865.

Thomas J. Brown is professor of history at the University of South Carolina.

Thomas J. Brown is professor of history at the University of South Carolina.

[1] Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). For a vivid description of the fire, see Charles Royster, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), chap. 1.

[2] I discuss the local performance of victimhood in Thomas J. Brown, “Monuments and Ruins: Atlanta and Columbia Remember Sherman,” Journal of American Studies 51 (May 2017): 411-436.

[3] W. Eric Emerson, “Commemoration, Conflict, and Constraints: The Saga of the Confederate Battle Flag at the South Carolina State House,” in Interpreting the Civil War at Museums and Historic Sites ed. Kevin M. Levin (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 87.