Mushroom of the Month, August 2018: Ravenel’s Stinkhorn Phallus ravenelii

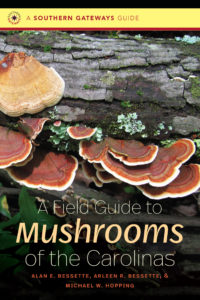

Here’s the next entry in our monthly series, Mushroom of the Month, brought to you by Michael W. Hopping, co-author of A Field Guide to Mushrooms of the Carolinas: A Southern Gateways Guide — this month it’s Ravenel’s Stinkhorn Phallus ravenelii.

Here’s the next entry in our monthly series, Mushroom of the Month, brought to you by Michael W. Hopping, co-author of A Field Guide to Mushrooms of the Carolinas: A Southern Gateways Guide — this month it’s Ravenel’s Stinkhorn Phallus ravenelii.

Mushrooms in the wild present an enticing challenge: some are delicious, others are deadly, and still others take on almost unbelievable forms. A Field Guide to Mushrooms of the Carolinas introduces 650 mushrooms found in the Carolinas–more than 50 of them appearing in a field guide for the first time–using clear language and color photographs to reveal their unique features.

A Field Guide to Mushrooms of the Carolinas is available now in both print and ebook editions.

Look for more Mushroom of the Month features on the UNC Press Blog in the months ahead.

###

Ravenel’s Stinkhorn Phallus ravenelii

In the life sciences, the practice of naming a new species in honor of a colleague, the use of an eponym, goes way back. Eponyms don’t help anyone picture the species in question, but that’s usually the worst that can be said of them. There are, however, exceptions. Two 19th century pillars of Carolinas mycology were involved in what surely ranks among the most backhanded eponymic compliments in history.

Rev. Moses Ashley (M. A.) Curtis, an Episcopal priest and amateur botanist based in Hillsborough, published his first mushroom paper in 1848. Later, during a church assignment in Society Hill, SC, he began a long-distance collaboration with the English mycologist, Rev. Miles Joseph Berkeley. It was highly productive. Few author citations for mushroom species are as common as the abbreviation, Berk. & M.A. Curtis.

Curtis had a friendly rival for the unofficial title of greatest American mycologist of the day. South Carolina plantation owner Henry William Ravenel staked his claim in the 1850s with 5-volume sets of dried fungi, collectively known as Fungi Caroliniani Exsiccati. Each volume contained 100 specimens hand-glued to the pages. (The set he provided to the Smithsonian became a foundational contribution to the National Fungus Collection in Beltsville, Maryland.) Throughout Ravenel’s mycological career he also worked with Berkeley and Curtis.

Each of these men had several species named after him. But two eponyms bestowed on Ravenel by Berkeley and Curtis stand out; they were for new stinkhorns.

Stinkhorns are the preadolescent boys of the mushroom world. They glory in producing a foul smelling, spore containing, olivaceous goo. Flies wade around in it, eating their fill before buzzing off to track spores elsewhere. Stinkhorns “hatch” from rounded eggs, then assume shapes ranging from the fantastically improbable to blatantly phallic. Both species honoring Ravenel fall into the latter category. Mutinus ravenelii has a pitted and pink shaft with a slightly bulbous, gooey head. Ravenel himself had been first to collect the other variety in 1846, but Berkeley and Curtis waited decades before announcing it to the world as Phallus ravenelii.

Ravenel’s Stinkhorn is hard to miss, fruiting on or near rotting wood. The stench is detectable at a distance. Add to that the startling shape and size, to 16 cm tall. The hollow, white stalk is tipped by a round opening and goo-slathered skirt. All of this hatches from an odorless, pink egg up to 4.5 cm in diameter. A cup-shaped remnant of it persists at the base of the shaft. Adventurous eaters have sampled stinkhorn eggs. Reports of that experience are generally not glowing, and the practice isn’t recommended.

Social etiquette has evolved since Phallus ravenelii got its name in 1882, but still. Just how fond of Ravenel were Berkeley and Curtis? Were the questionable eponyms displays of British vicar humor? Berkeley named a phallic stinkhorn after Curtis too. And although Curtis officially co-authored Phallus ravenelii, Berkeley had had to resurrect his recently deceased partner for the occasion. Now, with all three of the old pals in heaven, one wonders whether they ever tire of debating the line between honor and mockery in the naming of mushrooms.

Who won out as the greatest American mycologist of the mid-19th century? If stinkhorns are the measure of the man, Ravenel beat Curtis by a score of two to one.

###

Michael W. Hopping, a retired physician and author, is a principal mushroom identifier for the Asheville Mushroom Club. You can read his previous blog posts here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.