Celebrity and Crazy

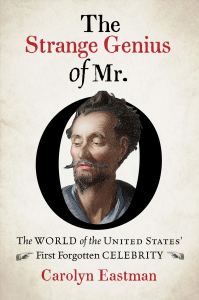

The following is a guest blog post by Carolyn Eastman, author of The Strange Genius of Mr. O: The World of the United States’ First Forgotten Celebrity, published by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press. The Strange Genius of Mr. O. is the biography of a remarkable performer—a gaunt Scottish orator who appeared in a toga—and a story of the United States during the founding era.

Do the pressures of stardom drive people crazy?

Considering all we know about performers’ breakdowns and drug rehab stays, it’s shocking that more of them haven’t rebelled against the constant pressure of the public eye the way that Simone Biles, the world’s top gymnast, and Naomi Osaka, the world #2 tennis player, recently discussed. When Biles withdrew from team competition at the summer Olympics, and Osaka announced earlier this month that she would not participate in the French Open’s press conferences due to the emotional strain they caused, the resulting furor only compounded the stresses experienced by these athletes.

Superstars face scrutiny for everything, from their weight and fashion choices to their publicly-stated political positions. The recent documentary Framing Britney Spears (2021) reminded us of Britney Spears’s alleged “meltdown” from 2007 when, followed night and day by paparazzi, she rushed into a barber shop one day and shaved off her blonde hair, believing they’d stop taking photos of her if she did. “SHEAR MADNESS,” the New York Post’s headlinescreamed above a series of new photos of Spears’ butchered hair. We were led to believe that celebrity had driven her crazy; famously, the courts have treated her as irresponsible ever since.

While it would be tempting to ascribe such stressors to the particular nature of 21st-century celebrity culture, looking back to an American celebrity of the early 19th century reveals some of the same stress—the emotional toll of having to perform, constantly, in every setting.

Things certainly looked different more than 200 years ago, a period of American history that predated paparazzi, gossip rags, People, and even the reckless use of the word crazy. Nevertheless, as I found in developing my new book, The Strange Genius of Mr. O: The World of the United States’ First Forgotten Celebrity, I found people suffering from the toll taken by public life.

James Ogilvie, the “strange genius” at the center of my book, won his acclaim due to his explosive, riveting gift for eloquence in public speaking—lectures enacted on stage with unparalleled personal grace and emotional power. Starting in 1808 at the age of 35, he abandoned teaching and spent the rest of his life traveling from town to town giving speeches. Newspapers followed him closely, reporting on his triumphs as well as the scandals around him. Within a year of starting this unusual career, he had become a household name. He ultimately spent more than twelve years in a constant cycle of traveling and performing.

Like later celebrities, Ogilvie could never rest on his laurels. Above and beyond his exhausting stage performances, he had no management, so he was solely responsible for finding venues and housing, making travel arrangements, submitting advertisements to newspapers, and decorating the stage. He even often sold his own tickets.

Even when he wasn’t literally on stage, he needed to perform to appeal to benefactors—influential men and women whose approval guaranteed large audiences and flattering reviews. Gaining their support required constant energy, from knocking on the doors to seeking out invitations to dinners and parlor gatherings. Always a stranger, he had to adhere to the strictest rules of personal behavior with new acquaintances. Always a man on the make—that is, seeking potential supporters and attendees before leaving for a new locale—he never had the luxury of considering his acquaintances to be true friends.

He certainly succeeded. He gained the support of some of the country’s most prominent figures, including Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and Benjamin Rush, as well as a host of elite society women. But they also acknowledged that he could be weird. In 1809, the novelist Washington Irving, one of Ogilvie’s most vigorous defenders against naysayers in New York, called him a “philosophical Quixote … whose harmless eccentricities and visionary speculations” didn’t deserve attack.

The criticism exerted a toll. Only three years after starting his lecture tour, Ogilvie had to step away from the bustle in order to break his opium habit. (Getting clean didn’t last, however.) At other times, his own self-image diverged radically from that of his listeners. One evening he returned to the stage while the audience was still applauding, only to make a surprise announcement: he was so embarrassed about having forgotten an important passage that he promised to return the following night and repeat the lecture for free. “We were perfectly satisfied with the first delivery,” a writer for a magazine confessed, “till we were told by the orator himself that he had mangled it.” They cheerfully chalked it up to his eccentricity.

James Ogilvie’s career pre-dated the arrival of a full-blown celebrity culture in the United States, but the pressures he experienced led to familiar results. The drug habit, the narcissism, the increasingly erratic behavior—all have deep resonances for 21st-century celebrities and their efforts to retain emotional balance. They remind us that even the most accomplished stars struggle with the constant demand to perform.

Carolyn Eastman is associate professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University and the author of the prizewinning A Nation of Speechifiers: Making an American Public after the Revolution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.